J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., (2023), Vol. 13(2): 47–52

Original Research

10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i2.1

Retrospective study of 311 cases of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia with vascular access devices compared to ethnicity: Incidence in Waikato New Zealand from 2008-2018

Lynette J. Lennox* and Jenny Heretini

Waikato District Health Board, Hamilton, New Zealand

*Corresponding Author: Lynette J. Lennox. Waikato District Health Board, Hamilton, New Zealand. Email: lynette.lennox [at] waikatodhb.health.nz

Submitted: 26/04/2022 Accepted: 04/06/2023 Published: 30/06/2023

© 2023 Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives License(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

Abstract

Aim: To document retrospectively whether New Zealand (NZ) Māori have a higher incidence of health associated (HA) Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) with a vascular-access-device (VAD) compared to other ethnicities in Waikato District Health Board (WDHB).

Methods: From January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2018, all ages of inpatients with a VAD HA-SAB in one District Health Board (DHB) were retrospectively studied. All data was obtained from the Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) SAB records and analyzed.

Results: The study period of 11 years identified 311 VAD HA-SABs. The overall statistical hypothesis testing of VAD HA-SABs was p =0.175. A greater proportion of VAD HA-SABs occurred in the renal population at a rate of 35.7% (111). Renal representation of ethnic groups with a VAD HA-SAB were non-NZ Māori 52.86% and Māori 47.14%. Peripheral VAD had a greater percentage of incidence of VAD HA-SAB.

Conclusion: Māori renal patients with VAD’s in WDHB experienced an increased incidence of HA-SABs from 2008 to 2018 in comparison to other ethnic populations. Māori renal patients are 3½ times more likely to suffer VAD HA-SAB than non-Māori patients. NZ data for VAD HA-SABS requires IPC teams to include ethnicity and provide a standardized, correct diagnosis of a VAD HA-SABS. NZ health strategies need to ask well-directed questions in order to progress toward equitable health outcomes.

Keywords: Vascular access device, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacteremia, Indigenous and Māori.

Introduction

Study setting

New Zealand (NZ) is made up of two main islands in the South Western Pacific Ocean. The total population is approximately 4.9 million. The ethnic composition includes European 74% the indigenous population Māori 14.9% and other ethnicities. Most health care was funded by central government and managed by District Health Boards (DHB). Waikato District Health Board (WDHB) is 1 of 20 DHBs in NZ. It serves a population of around 420,000 and covers 21,000 square kilometers, including both rural and one city. WDHB serves the fourth highest Māori population group in all NZ DHBs being 14% of the general population (2013 QuickStats About National Highlights, 2019).

Vascular access

Modern-day treatment in health care requires dependable venous access. Insertion of a VAD is one of the most frequent invasive procedures within a hospital setting and is not without risk. Worldwide more than 1 billion peripheral vascular access devices (VADs) are inserted, cared for, and managed every year. Peripheral VADs are known to be the most used invasive device in the hospital. Up to 80% of all inpatients will receive at least one peripheral VAD for treatment (Zhang et al., 2016; Alexandrou et al., 2018). For every five health associated-Staphylococcus aureus, Bacteremia (HA-SABs) that occur in NZ, one is directly related to a peripheral VAD (Turnidge et al., 2009). VADs carry associated risks and complications that can result in permanent harm, extended stay in the hospital, increased cost to an organization, and distress to the patient and family (Zhang et al., 2016; Alexandrou et al., 2018).

Infection, leading to a HA-SAB is one type of VAD complication. All HA-SABs are monitored and reported to the Health Quality Safety Commission (HQSC) and the Ministry of Health (MOH). The cost of an NZ SAB is approximately $20,394 (Burns et al., 2010; Health Quality & Safety Commission, 2018). Types of VAD that can develop HA-SABs include, peripheral, arterial, central VAD, and renal. VADs required for renal patients include three types. They are, a Permacath, short-term Vascath and lastly, fistulae (Schmidli et al., 2018).

Studies both internationally and within NZ demonstrate that HA-SABs are a leading complication associated with insertion, management, and removal of VADs. Research from NZ suggests that 8% of all HA-SABS are related to a VAD (Greiner et al., 2007; Turnidge et al., 2009; Burns et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Alexandrou et al., 2018; Health Quality & Safety Commission, 2018; Schmidli et al., 2018). Studies have shown that, excluding Pasifika, Māori may have up to three times the HA-SAB infection rate of NZ European (Hill et al., 2001; Williamson et al., 2013; Williamson et al., 2014).

The HQSC 2017 guide used by NZ Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) nurse teams provides a HA-SAB definition with six criteria. The first criterion is the patient acquired HA-SAB whilst in a DHB hospital. The second, the first confirmed blood culture is not within 48 hours of admission. Third, it is related to a confirmed complication from an indwelling device such as a VAD. Fourth, the HA-SAB may occur within 30 days of surgery or procedure involving implantable devices. Fifth, it is diagnosed within 48 hours of an incision or invasive instrumentation. Sixth and lastly, it is associated with neutropenia (<1.0 × 109 /l) associated with chemotherapy treatment (Health Quality & Safety Commission, 2018).

In 2019 both the MOH and the HQSC have released reports focusing on achieving equity in health outcomes for Māori. These guidelines recommend the recording and monitoring of HA-SABs underpinning all work using the “Te Tiriti o Waitangi” framework. This closely relates to system-level approaches used internationally to collaborate long standing problems such as inequity of health outcomes (Health Quality Safety Commission, 2019; Ministry of Health, 2019). The aim of this retrospective study was to investigate whether Māori inpatients with VAD’s in Waikato DHB from 2008-2018 experienced increased incidence of HA-SABs in comparison to other ethnic populations. This will inform future studies that may assist in improving equitable health outcomes for Māori.

Materials and Methods

The researcher gathered all data from all the IPC HA-SABs from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2018. Extraction of WDHB VAD HA-SABs data required the filtering from all other types of HA-SAB infections. The data obtained, included four secondary rural hospitals and one tertiary hospital within the DHB. The analysis of all VAD HA-SABs included ethnicity, year, age, sex, department, and type of VAD. The analysis was to ascertain whether Māori experience a disproportionately higher incidence of VAD HA-SABs compared to other ethnicities.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the patient data using Microsoft Excel, descriptive statistics, and pivot tables.

Ethical approval

Local ethical approval for this study was sought but not required. The research strategy used was a retrospective cross-sectional observation analysis of all VADs with HA-SAB.

Results

WDHB admissions from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2018 total 1,172,461 inpatients. Generally accepted research states that up to 80% of all inpatients have a VAD. This would equate up to 937,969 patients in 11 years with a VAD (Zhang et al., 2016; Alexandrou et al., 2018). The researcher identified that all VAD HA-SABs from IPC data totaled 311 inpatients. All patients that had a VAD and an HA-SAB were included in the final data.

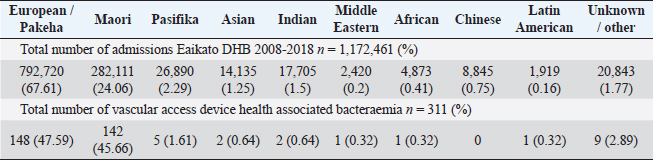

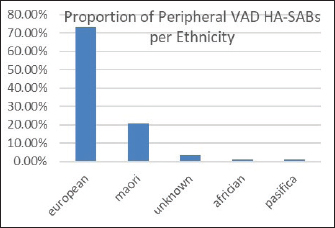

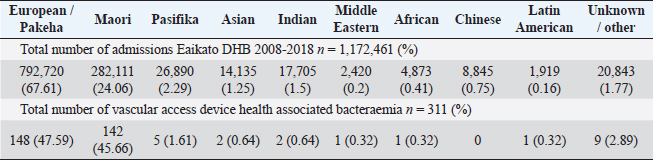

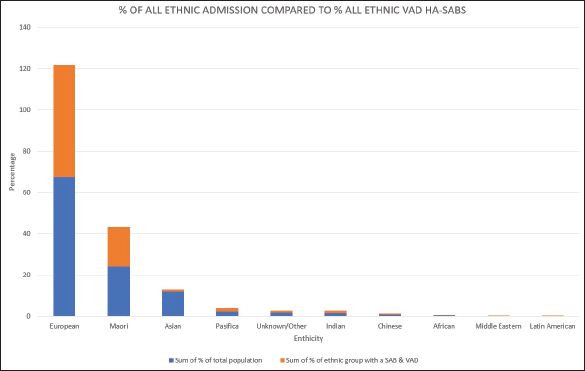

Table 1 and Figure 1 show the numbers of total inpatient admissions and VAD HA-SABs for all ethnic groups from 2008 to 2018. The total admissions for ethnicities were similar to the overall percentage of the population that live in the WDHB.

The overall percentage with a VAD HA-SAB from the total population of inpatients was 0.033%. When the total of 311 inpatients incidents were analyzed, the statistical probability of Māori compared to European of having an episode of a VAD HA-SAB is p =0.175. The sex of all 311 VAD HA-SABs were males 60% (186), females 39% (12), and 1% (4) unknown. The mean age of this group was 52 years, with minimum age <1 year and maximum age of 96 years.

Table 1. Total results for admissions from 2008 to 2018.

Fig. 1. Graph comparing percentages of overall admissions compared to overall VAD HA-SABs.

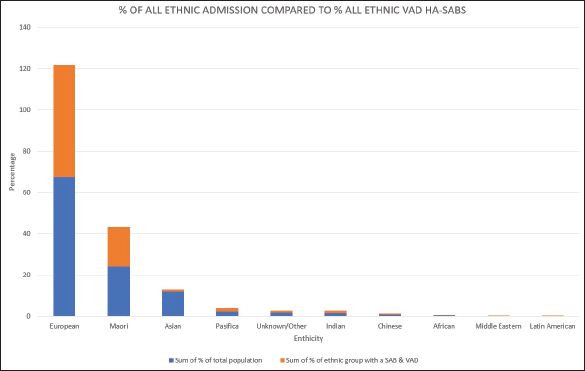

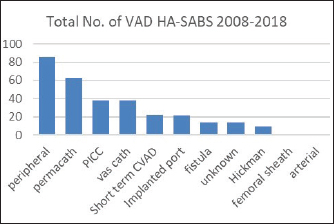

Fig. 2. Total number of VAD that resulted in a HA-SAB 2008–2018.

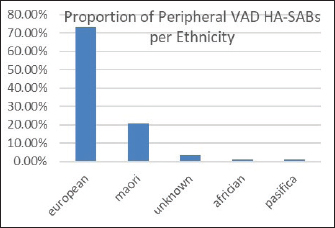

Fig. 3. Overall percentages of ethnic groups with a peripheral VAD HA-SABS.

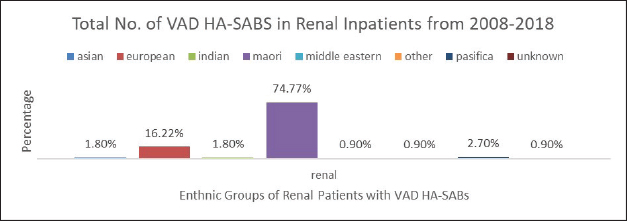

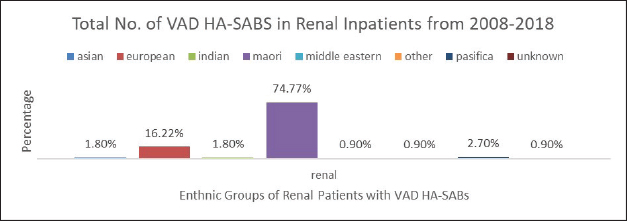

Fig. 4. Graph comparing percentages of all renal inpatients who resulted having a VAD.

The distribution of all clinical services having confirmed VAD HA-SABs were renal 35.7% (111), oncology/hematology 19% (59), surgical 15.8% (49), medical 9.6% (30), coronary care unit 7.7% (24), pediatrics 4.2% (13), neonatal intensive care 2.9% (9), intensive care unit 2.3% (7), high dependency unit 1.9% (6), old persons rehabilitation 0.6% (2) and emergency department 0.3% (1).

Peripheral VADs are the most used vascular device and our results in Figure 2 were similar at 27.65% of all VADs (Zhang et al., 2016; Alexandrou et al., 2018). The ethnic mix is reflected in Figure 3, it demonstrates that the proportion of the ethnic mix is consistent with the overall ethnic admission rates. The ethnic representation is within the proportion of overall admissions for the 11 years. Therefore, Māori do not have a higher rate of VAD HA-SABs with peripheral VADs.

However, the highest proportion of 36.6% of all VAD HA-SABs is shown to be with renal inpatients. These VADs include Permacath, Vascath, and Fistulae. The mix of ethnic population for all renal admissions from 2008 to 2018 show that 47.13% were Māori and Non-Māori were 52.86%. The rates of renal VAD HA-SABs are shown in Figure 4.

Discussion

In NZ HA-SABs are a considerable problem for all ethnicities including Māori. It is associated with a higher mortality (Hill et al., 2001; Turnidge et al., 2009; Burns et al., 2010; Williamson et al., 2013; Williamson et al., 2014; Tong et al., 2015). Our results have shown the incidence of VAD HA-SAB occurred at a rate of 0.033% or an average of 31 per year over all departments. The two largest ethnic groups identified were European and Māori. The statistical difference between the infection rates of Māori and European is not significant with p =0.175. The variation may indicate that the test group demonstrates some sampling error with the data collection.

Nonetheless, 35.7% of all VAD HA-SABs occur in renal patients. The proportion of Māori in renal with a VAD HA-SAB is considerably higher compared to all other ethnic groups. Māori renal inpatients had a total of 74.77% of all VAD HA-SABs compared to European having 16.22%. In total, Māori who had a renal VAD that resulted in an HA-SAB, had an incidence ratio of 1.59 compared to European being 0.45. Therefore, Māori renal patients are 3½ times more likely to develop VAD HA-SABs than European patients. The significance of the renal population demonstrates that Māori have a proportionately higher rate of VAD HA-SABs (Hill et al., 2001; Turnidge et al., 2009; Burns et al., 2010; Williamson et al., 2013; Tong et al., 2015).

We reviewed rates of peripheral VAD HA-SABs as these are the most common invasive device used for inpatients. The proportion of peripheral VADs HA-SAB in European and Māori was statistically insignificant.

As other studies have shown, our study showed that the incidence of VAD HA-SABs is higher in male inpatients compared to females (Hill et al., 2001; Williamson et al., 2013; Williamson et al., 2014). Additionally, the mean age of 52 years of age is also consistent with other studies (Hill et al., 2001; Williamson et al., 2013; Williamson et al., 2014).

Ethnicity inequality in indigenous populations around the world including Māori, continues to reflect higher rates of HA-SABs than European populations (Turnidge et al., 2009; Gessel et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2015). Our research identified the specific types of VAD HA-SABS. On the whole, our results find that Māori do not have a higher incidence of VAD HA-SABS, with the exception of renal inpatients with a VAD (Schmidli et al., 2018).

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study is 11 years of data providing the benefits of a detailed approach regarding VAD HA-SABs, rather than being pooled into a group of other sources of infection. These other types of HA-SABS include wounds, pneumonia, surgical site infections and other types of indwelling devices such as drains and indwelling catheters. The data has provided detail of VAD HA-SABs in the WDHB which has been compared to other NZ studies (Hill et al., 2001; Turnidge et al., 2009; Burns et al., 2010; Williamson et al., 2013; Williamson et al., 2014; Tong et al., 2015).

This retrospective study to establish our baseline data at WDHB was dependent on information from IPC, which showed some inconsistencies. Therefore, we were reliant on a correct diagnosis using the 2017 HQSC guidelines which, in some cases appears not to be the case. Furthermore, the grouping of all types of indwelling devices with VADs as a source of the HA-SAB with hospitalized patients probably causes limitations for identifying a definitive cause. To shine a light on the actual issue and thus provide an opportunity to improve outcomes, VAD HA-SABs need to be reported as a single cause.

Implications for further research

In order to find the answer to a problem first there is the need for NZ health strategies to be asking the right questions. NZ data for VAD HA-SABS requires IPC teams to include ethnicity and provide a standardized, correct diagnosis of a VAD HA-SABS. NZ national health strategies for 2019 have blind spots for VAD HA-SABs. To be inclusive of all types of infection, VADs need to have focused strategies to improve the inequalities in renal health care provision for Māori.

Since national public healthcare systems are financially challenged, ongoing research requires initiatives that are cost-effective. Most care and management of VADs are performed by nurses. Therefore, vigilant nursing care contributes to the reduction of VAD HA-SABs. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention 2011 guidelines for the reduction of VAD HA-SABs, recommend the following; All patients with a VAD should receive a daily wash or shower with chlorhexidine 2%, cleansing the skin to reduce the risk of an HA-SAB (O’Grady et al., 2011; Climo et al., 2013).

However, concern regarding the potential risks of chlorhexidine allergies has been identified by some studies (Vu et al., 2017; Paulela et al., 2018). Consequently, there is merit in considering the use of newly developed washcloths which are chlorhexidine and soap-free, that clean and protect the skin. Washcloths could potentially reduce the rates of VAD HA-SABs in renal Māori inpatients. Future studies could be considered to test this theory.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank and acknowledge the contribution of Victoria University, Wellington, NZ, particularly Deborah Nelson, Kevin Dittmer MIM for analysis, Waikato DHB business analysis team, IPC, and renal department.

References

2013 QuickStats About National Highlights. Available via http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/quickstats-about-a-place.aspx?request_value=13631&tabname= (Accessed 24 March 2019).

Alexandrou E., Ray-Barruel, G., Carr, P.J., Frost, S.A., Inwood, S., Higgins, N., in F, Alberto, L., Mermel, L. and Rickard CM; OMG Study Group. 2018. Use of short peripheral intravenous catheters: characteristics, management, and outcomes worldwide. J. Hosp. Med. [Internet]. 13(5). Available via https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/article/166494/hospital-medicine/use-short-peripheral-intravenous-catheters-characteristics (Accessed 26 March 2019).

Brown, E.L., Below, J.E., Fischer, R.S.B., Essigmann, H.T., Hu, H., Huff, C., Robinson, D.A., Petty, L.E, Aguilar, D., Bell, G.I. and Hanis, C.L. 2015. Genome-wide association study of Staphylococcus aureus carriage in a community-based sample of Mexican-Americans in Starr County, Texas. PLoS One. 10(11), e0142130.

Burns, A., Bowers, L., Pak N,T., Wignall, J. and Roberts, S. 2010. The excess cost associated with healthcare-associated bloodstream infections at Auckland City Hospital. N. Z. Med. J. (Online) Christchurch 123(1324), 17–24.

Gessel, H.V., McCann, R.L, Peterson, A.M. and Goggin, L.S. 2010. Validation of healthcare-associated Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection surveillance in Western Australian public hospitals. Healthc. Infect. 15(1), 21–25.

Greiner, W., Rasch, A., Köhler, D., Salzberger, B., Fätkenheuer, G. and Leidig, M. 2007. Clinical outcome and costs of nosocomial and community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection in haemodialysis patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13(3):264–268.

Hill, P.C., Birch, M., Chambers, S., Drinkovic, D., Ellis-Pegler, R.B., Everts, R., Murdoch, D., Pottumarthy, S., Roberts, S.A., Swager, C., Taylor, S.L., Thomas, M.G., Wong, C.G. and Morris, AJ. 2001. Prospective study of 424 cases of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: determination of factors affecting incidence and mortality. Int. Med. J. 31(2), 97–103.

Health Quality Safety Commission. A window on the quality of Aotearoa New Zealand’s health care 2019 – a view on Māori health equity [Internet]. Health quality & safety commission. 2021. Available via https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/resources/resource-library/a-window-on-the-quality-of-aotearoa-new-zealands-health-care-2019-a-view-on-maori-health-equity-2/ (Accessed 31 July 2019).

Ministry of Health. Achieving equity in health outcomes: summary of a discovery process. 2019. Available via https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/achieving-equity-health-outcomes-summary-discovery-process (Accessed 29 July 2019).

Health Quality & Safety Commission. National approach for healthcare associated infection quality improvement [Internet]. Health Quality & Safety Commission. Available via https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/news/national-approach-for-healthcare-associated-infection-quality-improvement/ (Accessed 30 July 2018).

O’Grady, N.P, Alexander, M., Burns, L.A, Dellinger, E.P., Garland, J., Heard, S.O., Lipsett, P.A., Masur, H., Mermel, L.A., Pearson, M.L, Raad, I.I., Randolph, A.G., Rupp, M.E. and Saint, S; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). 2011. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52(9), e162–e193.

Paulela, D.C., Bocchi, S.C.M., Mondelli, A.L., Martin, L.C. and Sobrinho, A.R. 2018. Effectiveness of bag bath on microbial load: clinical trial. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 31(1), 7–16.

Schmidli, J., Widmer, M.K., Basile, C., Donato, G de., Gallieni, M., Gibbons, C.P., Haage, P., Hamilton, G., Hedin, U., Kamper, L, Lazarides MK, Lindsey B, Mestres G, Pegoraro M, Roy J, Setacci C, Shemesh D, Tordoir JHM, van Loon M., Esvs Guidelines Committee, Kolh P., de Borst GJ., Chakfe N., Debus S., Hinchliffe R., Kakkos S., Koncar I., Lindholt J., Naylor R., Vega de Ceniga M., Vermassen F., Verzini F., Esvs Guidelines Reviewers, Mohaupt M., Ricco JB. and Roca-Tey R. 2018. Editor’s choice—vascular access: 2018 clinical practice guidelines of the European society for vascular surgery (ESVS). Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 55(6), 757–818.

Tong, S., Davis, J., Eichenberger, E., Holland, T. and Fowler, V. 2015. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 603–661.

Turnidge, J.D., Kotsanas, D., Munckhof, W., Roberts, S., Bennett, CM., Nimmo, G.R., Coombs, G.W., Murray, R.J., Howden, B., Johnson, P.D. and Dowling K; Australia New Zealand Cooperative on Outcomes in Staphylococcal Sepsis. 2009. Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: a major cause of mortality in Australia and New Zealand. Med. J. Aust. 191(7) 368–373.

Vu, M., Rajgopal Bala, H., Cahill, J., Toholka, R. and Nixon, R. 2017. Immediate hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine. Aust. J. Dermatol. 59(1), 55–56.

Williamson, D.A., Lim, A., Thomas, M.G., Baker, M.G., Roberts, S.A., Fraser, J.D. and Ritchie SR. 2013. Incidence, trends and demographics of Staphylococcus aureus infections in Auckland, New Zealand, 2001–2011. BMC Infect. Dis. 13(1), 569.

Williamson, D.A., Zhang, J., Ritchie, S.R., Roberts, S.A., Fraser, J.D. and Baker MG. 2014. Staphylococcus aureus infections in New Zealand, 2000–2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20(7), 1156–1161.

Zhang, L., Cao, S., Marsh, N., Ray-Barruel, G., Flynn, J., Larsen, E. and Rickard, CM. 2016. Infection risks associated with peripheral vascular catheters. J. Infect. Prev. 17(5), 207–213