| Case Report | ||

J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., (2024), Vol. 14(1): 34–37 Case Report Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case reportShankar Lal1, Afreen Siddiqui2, Lamis Ibrahim1 and Dima Youssef1*1Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN 2East Tennessee State University, Quillen College of Medicine, Johnson City, TN *Corresponding Author: Youssef D. Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN. Email: estecina [at] hotmail.com Submitted: 06/02/2024 Accepted: 24/03/2024 Published: 31/03/2024 © 2024 Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

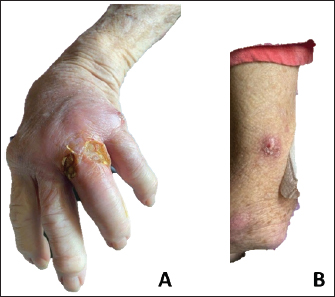

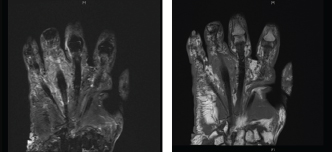

ABSTRACTBackground: Mycobacterium chelonae, a rapidly proliferating nontuberculous Mycobacterium, is renowned for instigating diverse infections, notably those affecting the integumentary system. Despite its pervasive presence in the environment, its propensity for pathogenicity in human hosts often eludes recognition. In this case report, we endeavor to provide a thorough exposition encompassing the epidemiological characteristics, clinical presentations, diagnostic modalities, and therapeutic strategies pertinent to M. chelonae infections, with particular emphasis on its manifestations in skin and soft tissues. Case Description: We describe the case of an immunocompromised patient with a history of rheumatoid arthritis who presented with a 4-month history of erythematous nodules that started from her left hand and later extended up that arm. A diagnosis was not made until mycobacterial cultures grew M. Chelonae. The patient was treated with a 6-month course of antibiotics, including tigecycline and azithromycin, which resulted in a significant reduction of her cutaneous lesions. Conclusion: This report discusses the presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of M. Chelonae, a rare nontuberculous Mycobacterium that presented as a skin infection in an immunocompromised patient. Early recognition followed by treatment with appropriate antibiotics is crucial in reducing its spread to disseminated infections. Keywords: Mycobacterium chelonae, Skin nodules, Immunocompromised patient. IntroductionMycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous Mycobacterium typically found in soil, dust, and natural water supplies. Mycobacterium Chelonae infections can be acquired by environmental exposure by inhalation of aerosols or traumatic inoculation. Disease manifestations can vary depending on the patient’s immunity status. In immunocompetent patients, M. Chelonae can present as cellulitis and abscesses. In immunosuppressed patients, it can lead to disseminated diseases, such as endocarditis, lymphadenitis, and catheter-related infections. Diagnosis is challenging as clinical manifestations vary in each patient and histopathological findings can be nonspecific. Our case highlights the importance of recognizing M. Chelonae infections early and treating these cases with an extended course of appropriate antibiotics. Case DetailsA 79-year-old immunocompromised female with a history of psoriatic, osteo, and rheumatoid arthritis presented with a 4-month history of erythematous nodules that started from her left hand and extended up to her arm. The patient was first seen in the clinic several months earlier by her rheumatologist, who was initially concerned about a sporotrichosis infection, given the lymphadenopathic location of her wounds and her habit of working in rose bush gardens. She was treated with multiple antibiotics, including itraconazole, doxycycline, and cefdinir, without improvement. Several months later, she presented to the emergency department with worsening of the nodules, now associated with pain and purulent drainage. The patient denied fever, chills, or other constitutional symptoms. On physical examination, multiple 1–2 cm full-thickness ulcerations with necrotic tissue, yellow purulent drainage, and surrounding erythema and swelling were noted near the left fourth MCP joint. Several more violaceous and excoriated nodules and papules were present on the left arm (Fig. 1). The wounds and surrounding skin were moderately erythematous, and there were no signs of regional lymphadenopathy. The rest of the history and examination was unremarkable. X-ray of the left hand showed extensive diffuse arthritis involving joints of the hand and wrist without acute displaced fractures. MRI of the left hand revealed soft tissue swelling and dorsal soft tissue ulcerations in the proximal fourth finger with periosteal reaction and marrow signal abnormalities throughout the fourth metacarpal and fourth proximal phalanx compatible with osteomyelitis. There was also a questionable presence of a volar soft tissue abscess or phlegmon in the base of the fourth finger (Fig. 2). The MRI findings were seen among the background of diffuse arthritis with imaging features compatible with history of psoriatic arthritis. Acid-fast bacillus cultures from earlier grew Mycobacterium species and were sent to the state laboratory for specific species identification. Skin biopsy at the site revealed granulomatous reaction, acute inflammation, and keratin debris, and was negative for definitive infections.

Fig. 1. (A) Multiple 1-2cm punched out, ulcerated nodules with associated erythema near the left fourth MCP joint. (B) Multiple 2-3cm, red erythematous nodules and papules extending up patient’s left arm.

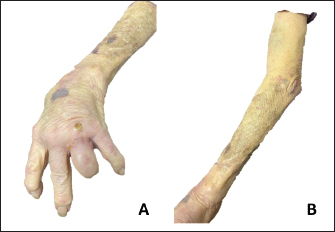

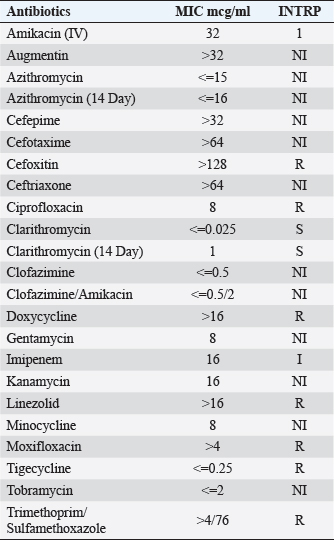

Fig. 2. Periosteal reaction and marrow signal abnormalities throughout the fourth metacarpal and fourth proximal phalanx suggestive of osteomyelitis. During admission, the patient was initially on intravenous vancomycin and cefepime. Wound cultures grew atypical mycobacteria (M. chelonae vs. Mycobacterium abscessus), and she was started on IV imipenem 500 mg q12 hours, IV amikacin 750 mg q48 hours, and p.o. Levaquin 500 mg daily. She was later discharged on IV imipenem, IV amikacin, and p.o. moxifloxacin 400 mg daily for 6 weeks. At her outpatient follow-up visit, after state labs came back positive for M. chelonae, and when the susceptibilities were performed (Table 1), we switched her antimicrobial therapy to IV tigecycline 50 mg every12 hours and oral azithromycin for 5 months, with continuous improvement and subsequent healing of ulcerations (Fig. 3). Azithromycin had to be stopped a little earlier because it worsened her hearing loss. To date, no recurrences have been observed on follow-ups, and the immunosuppressive therapy she was receiving for psoriatic arthritis and RA remains suspended. DiscussionThe clinical presentation of M. Chelonae infections exhibits a broad spectrum of variability, rendering accurate diagnosis challenging. Cutaneous manifestations may manifest as red or purple-hued papules or patches, pustules, folliculitis, or inflammation of the subcutaneous fat layer (Chang et al., 2004; Cusumano et al., 2017; Misch et al., 2018). In uncommon instances, the infection may adopt a “sporotrichosis” pattern, spreading through the subcutaneous lymphatic vessels from the point of entry. As the disease progresses, skin lesions may evolve into erosions or ulcers (Chang et al., 2004; Cusumano et al., 2017; Misch et al., 2018). In rare instances, constitutional symptoms such as fever may accompany the disease (Gonzalez-Santiago et al., 2015). Comprehensive patient history and skin biopsies obtained from representative lesions are imperative for histological examination and analysis of microbacterial cultures. Histopathological analysis typically reveals nonspecific rather than pathognomonic features, such as acute inflammation, micro abscess formation, granulomatous lesions (with or without caseation), and reactive changes in blood vessels, when employing routine staining methods like hematoxylin and eosin (Akram, 2023). Acid-fast staining, such as Ziehl-Neelsen staining, is indispensable for identifying acid-fast bacilli (Greenwood 1973). Furthermore, bacterial cultures tailored specifically for mycobacteria are essential for accurate species identification. Conventional bacterial cultures do not include mycobacterial detection, necessitating prolonged incubation periods for mycobacterial culture (Hay 2009). Molecular techniques such as PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism can identify nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), but they do not differentiate between M. chelonae and other species (Cusumano et al., 2017). Similarly, high-performance liquid chromatography alone cannot distinguish M. chelonae from M. abscessus (Fite 1938). However, the PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis has emerged as a promising tool, effectively differentiating NTM species and specifically identifying M. chelonae (Wallace et al., 1985; Saifi et al., 2013). This technique holds the potential for detecting the causative agent accurately. In our patient, the diagnosis of M. Chelonae cutaneous infection has been made through the presence of granulomatous inflammation on skin biopsy and on the AFB culture of a wound swab. Her AFB stain on skin biopsy was negative and this is perhaps related to the fact that immunosuppression can modify the histology of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections (Li et al., 2017).Rheumatological diseases such as RA may predispose patients to opportunistic infections through either innate immune dysregulation, or through immunosuppression medications. And atypical mycobacteria constitute an important group of opportunistic infections taking advantage of this patient group. A case report and review of the literature by Pham et al. (2023) identified that 64% of RA patients who developed M. Chelonae infection were treated with oral corticosteroids at the time of infection (Pham et al., 2023). Our patient has been treated with high doses of prednisone as part of her therapy and she has been on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Additionally, septic arthritis secondary to M. chelonae infection has been reported in 16% of infection cases (Pham et al., 2023). In our patient, her imaging suggested the presence of diffuse arthritis secondary to psoriatic arthritis and as such the possibility of septic arthritis due to M. Chelonae has not been confirmed, however she definitely had osteomyelitis as seen on the MRI imaging. She has been referred to a hand surgeon for evaluation of possible need for a potential surgical intervention viewing the presence of osteomyelitis, they however recommended to continue with the medical management with frequent monitoring of the stability of her metacarpophalangeal joints.

Fig. 3. (A) (B) Improvement of skin lesions approximately 4 months after initiation of antibiotic therapy. Mycobacterium chelonae infections are typically managed by administering a combination of at least two antimicrobial agents demonstrating in vitro efficacy against the specific isolate, sustained for a duration of no less than 4 months (Wallace et al., 1993; Wallace et al., 1985). For cases involving limited skin infection, the therapeutic approach involves the selection of two oral agents guided by susceptibility testing. From the available options including Bactrim, doxycycline, levofloxacin, and Clarithromycin or azithromycin, the selection of therapy should be based on the results of susceptibility testing. Moreover, in cases of severe infection caused by M. chelonae, it is recommended to initiate therapy with a combination of three agents, incorporating one to two intravenous agents, all of which demonstrate susceptibility against the isolate. Typically, treatment with this initial regimen should be continued until clinical improvement becomes apparent, a period typically ranging from 2 to 6 weeks. Subsequently, treatment should be transitioned to a therapeutic regimen comprising two to three oral agents, all of which exhibit in vitro activity against the pathogen. In our patient, it was challenging to treat her with several agents viewing the susceptibility pattern of the M. chelonae isolate she had. It was only susceptible to tobramycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin, minocycline, and tigecycline (Table 1). Side effects of therapy for atypical mycobacteria make it challenging and hard along the way to treat these infections. Several of these antibiotics have affected her hearing (tobramycin, macrolides), and Minocycline and tigecycline caused her dizziness and falls. However, the regimen she was able to tolerate the most was the intravenous tigecycline infusions. She had to be treated with this antibiotic on its own for 5 months and it was stopped when she achieved complete resolution of the skin lesions. Besides the antimicrobial therapy, the disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs have to be reduced and the duration of the antibiotics need to be extended (Fraenkel et al., 2021). In our patient, she has been taken off of all the DMARDs she has been on and she is maintained on a low dose of prednisone at 5 mg daily. Table 1. Susceptibility pattern of the M. Chelonae isolate. S=susceptible. R=resistant. I=intermediate, NI: no CLSI Interpretive guidelines for this antibiotics/organism combination.

ConclusionSkin and soft tissue infections caused by the rapidly growing nontuberculous Mycobacterium M. chelonae remain a rare dermatological occurrence. It is imperative that further studies and cases be reported to enhance awareness of this disorder. Notably, achieving a timely and accurate diagnosis continues to pose a challenge. Therefore, when suspicion arises, it is essential to perform a biopsy of the affected skin lesion to obtain tissue for histopathological examination, including acid-fast staining, routine bacterial culture, and mycobacterial culture with prolonged incubation periods, to facilitate the detection of the bacilli and ensure a precise diagnosis. Particularly, healthcare providers should consider NTM infections in the differential diagnoses of persistent and refractory skin lesions or ulcerations, especially following trauma, surgical interventions, or cosmetic procedures, in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. Upon confirmation of diagnosis, appropriate culture-directed treatment is imperative for effective management. AcknowledgmentsNone. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. FundingNone. Data availabilityAll data are provided in the manuscript. Authors contributionsAll authors contributed to this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. ReferencesAkram, S.M., Rathish, B. and Saleh, D. 2023. Mycobacterium chelonae infection. [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Chang, M.A., Jain, S. and Azar, D.T. 2004. Infections following laser in situ keratomileusis: an integration of the published literature. Surv. Ophthalmol. 49(3), 269–280. Cusumano, L.R., Tran, V., Tlamsa, A., Chung, P., Grossberg, R., Weston, G. and Sarwar, U.N. 2017. Rapidly growing Mycobacterium infections after cosmetic surgery in medical tourists: the Bronx experience and a review of the literature. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 63, 1–6. Fite, G.L. 1938. The staining of acid-fast bacilli in paraffin sections. Am. J. Pathol. 14(4), 491–507. Fraenkel, L., Bathon, J.M., England, B.R., St Clair, E.W., Arayssi, T., Carandang, K., Deane, K.D., Genovese, M., Huston, K.K., Kerr, G., Kremer, J., Nakamura, M.C., Russell, L.A., Singh, J.A., Smith, B.J., Sparks, J.A., Venkatachalam, S., Weinblatt, M.E., Al-Gibbawi, M., Baker, J.F., Barbour, K.E., Barton, J.L., Cappelli, L., Chamseddine, F., George, M., Johnson, S.R., Kahale, L., Karam, B.S., Khamis, A.M., Navarro-Millán, I., Mirza, R., Schwab, P., Singh, N., Turgunbaev, M., Turner, A.S., Yaacoub, S. and Akl, E.A. 2021. American college of rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis. Care. Res (Hoboken). 73(7), 924–939. Gonzalez-Santiago, T.M. and Drage, L.A. 2015. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol. Clin. 33(3), 563–577. Greenwood, N. and Fox, H. 1973. A comparison of methods for staining tubercle bacilli in histological sections. J. Clin. Pathol. 26(4), 253–257. Hay, R.J. 2009. Mycobacterium chelonae--a growing problem in soft tissue infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 22(2), 99–101. Li, J.J., Beresford, R., Fyfe, J. and Henderson, C. 2017. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J. Cutan. Pathol. 44(5), 433–443. Misch, E.A., Saddler, C. and Davis, J.M. 2018. Skin and soft tissue infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 20(4), 6. Pham, J.P., Boot, M., Stefani, M., Chapman, S., Byrne, A., Abdel-Shaheed, C., Girgis, L. 2023. Disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection complicating rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 26(6), 1167–1171. Saifi, M., Jabbarzadeh, E., Bahrmand, A.R., Karimi, A., Pourazar, S., Fateh, A., Masoumi, M. and Vahidi, E. 2013. HSP65-PRA identification of non-tuberculosis mycobacteria from 4892 samples suspicious for mycobacterial infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19(8), 723–728. Wallace, R.J. Jr, Swenson, J.M., Silcox, V.A. and Bullen, M.G. 1985. Treatment of nonpulmonary infections due to Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonei on the basis of in vitro susceptibilities. J. Infect. Dis. 152(3), 500–514. Wallace, R.J. Jr, Tanner, D., Brennan, P.J. and Brown, B.A. 1993. Clinical trial of clarithromycin for cutaneous (disseminated) infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae. Ann. Intern. Med. 119(6), 482–486. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Lal S, Siddiqui A, Ibrahim L, Youssef D. Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case report. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024; 14(1): 34 -37 . doi:10.5455/JMID.2024.v14.i1.6 Web Style Lal S, Siddiqui A, Ibrahim L, Youssef D. Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case report. https://www.jmidonline.org/?mno=192293 [Access: June 30, 2025]. doi:10.5455/JMID.2024.v14.i1.6 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Lal S, Siddiqui A, Ibrahim L, Youssef D. Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case report. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2024; 14(1): 34 -37 . doi:10.5455/JMID.2024.v14.i1.6 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Lal S, Siddiqui A, Ibrahim L, Youssef D. Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case report. J Microbiol Infect Dis. (2024), [cited June 30, 2025]; 14(1): 34 -37 . doi:10.5455/JMID.2024.v14.i1.6 Harvard Style Lal, S., Siddiqui, . A., Ibrahim, . L. & Youssef, . D. (2024) Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case report. J Microbiol Infect Dis, 14 (1), 34 -37 . doi:10.5455/JMID.2024.v14.i1.6 Turabian Style Lal, Shankar, Afreen Siddiqui, Lamis Ibrahim, and Dima Youssef. 2024. Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case report. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 14 (1), 34 -37 . doi:10.5455/JMID.2024.v14.i1.6 Chicago Style Lal, Shankar, Afreen Siddiqui, Lamis Ibrahim, and Dima Youssef. "Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case report." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 14 (2024), 34 -37 . doi:10.5455/JMID.2024.v14.i1.6 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Lal, Shankar, Afreen Siddiqui, Lamis Ibrahim, and Dima Youssef. "Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case report." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 14.1 (2024), 34 -37 . Print. doi:10.5455/JMID.2024.v14.i1.6 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Lal, S., Siddiqui, . A., Ibrahim, . L. & Youssef, . D. (2024) Shedding light on Mycobacterium chelonae and its cutaneous intrusion: A case report. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 14 (1), 34 -37 . doi:10.5455/JMID.2024.v14.i1.6 |